Maine Warned Public About a Measles Case — But Didn’t Mention It Was Caused by the Vaccine

A case of measles in 2023, reported by the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and mainstream media as being the state’s first case in four years, was vaccine-induced.

A case of measles in 2023, reported by the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and mainstream media as being the state’s first case in four years, was vaccine-induced, according to documents released Tuesday by Informed Consent Action Network (ICAN).

Kim Mack Rosenberg, general counsel for Children’s Health Defense, told The Defender that measles “outbreaks” are a well-worn tactic of state and federal governmental agencies to churn up fears about people who choose not to vaccinate or who do so selectively.

“We have seen measles used this way over and over,” Mack Rosenberg said. “Here, the narrative backfired and Maine officials swept under the rug the fact that the child’s measles strain was vaccine-related.”

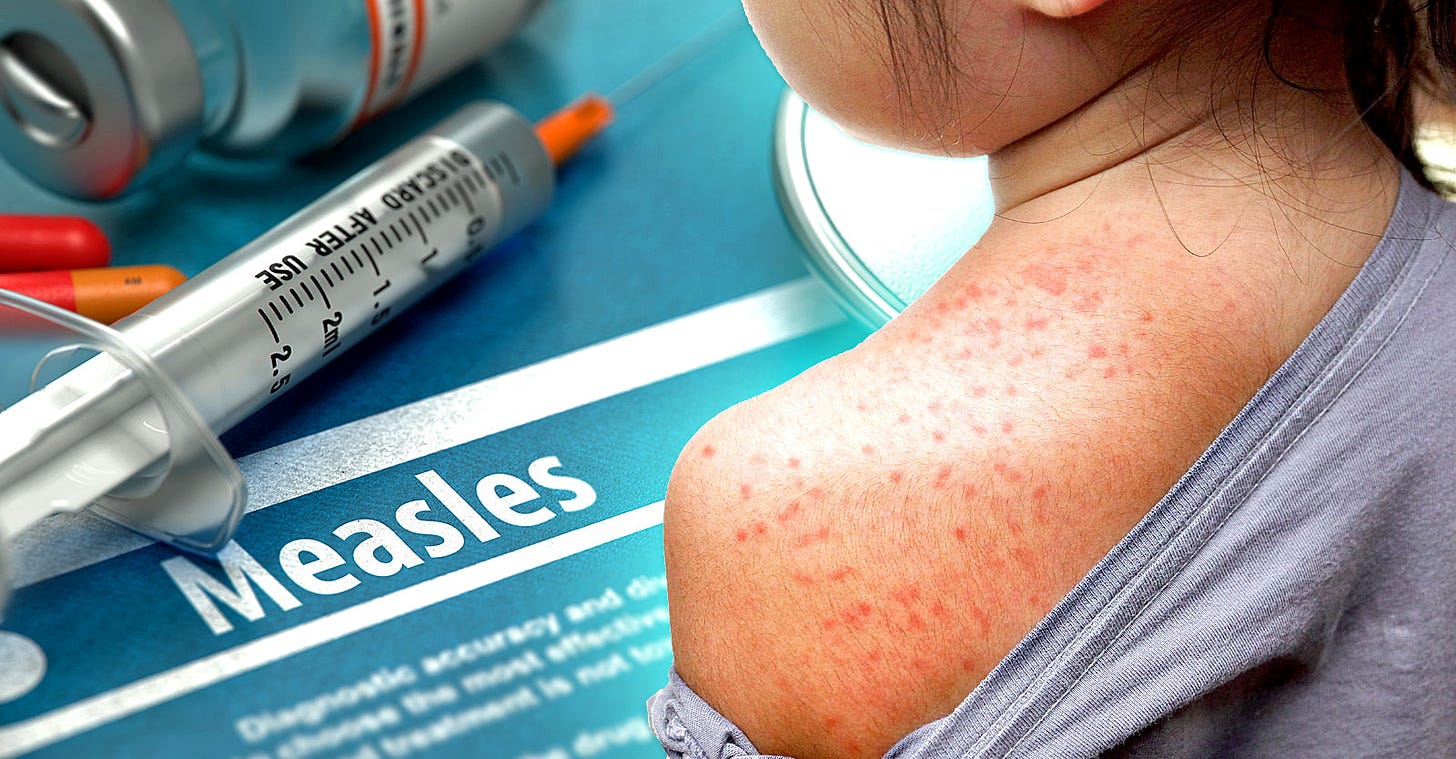

According to the Mayo Clinic, measles is a viral infection typically accompanied by a skin rash, fever, cough, runny nose, sore throat, inflamed eyes and tiny white spots on the inner cheek.

On May 5, 2023, Maine’s Department of Health and Human Services warned that the Maine CDC had been notified of a positive measles test — ostensibly the state’s first measles case since 2019.

The health department said the child “received a dose of measles vaccine” and that Maine CDC officials were “considering the child to be infectious out of an abundance of caution.”

The news was quickly picked up by mainstream news outlets such as CNN, which blamed low vaccination rates for recent measles outbreaks, and USA Today, which stressed that the best way to prevent measles is for children and babies as young as 12 months to get the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine.

However, the child’s May 3, 2023, test results — which ICAN obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request — revealed that the measles strain was “consistent with vaccine strain” — meaning the vaccine caused the child’s rash symptoms.

Roughly 2% of people who get a measles vaccine develop a rash, according to a World Health Organization report. But the Maine CDC never went public about this information.

Nearly two weeks after the testing was done, the Maine CDC on May 16, 2023, announced that the child didn’t have an infectious strain of measles — but the announcement failed to state that the child’s rash was vaccine-related.

Why did the Maine CDC take so long to confirm the strain?

It’s inexcusable that Maine CDC officials took so long to determine the strain of measles, Mack Rosenberg said.

“Their fear is that such information would lead to more vaccine hesitancy,” she said. “However, obfuscating information in this way deprives the public of crucial information about vaccine safety and effectiveness.”

ICAN in a press release questioned why the Maine CDC raised the alarm and then took so long to confirm the specific strain.

Mack Rosenberg noted that mainstream news outlets “immediately” jumped on “the fearmongering bandwagon” before the strain type was identified.

“Yet when the true nature of this child’s exposure was revealed,” she said, ”ranks were closed to prevent the truth from getting out.”

Karl Jablonowski, Ph.D., a senior research scientist at CHD, told The Defender it was “reckless fear-mongering” to identify one case of measles in a vaccinated child and then issue a press release saying that anyone who isn’t immunized against measles, or doesn’t know their immunization status, should get vaccinated.

“Fear-mongering is formulaic: danger, solution and vilify those who do not conform,” he said.

If it’s well executed and done in coordination with media, it may get people to do what you want — but at a cost, he said. “One of the greatest threats to our public health is that our public health institutions lack integrity.”

Reports of measles outbreaks continue

Reports of measles outbreaks have continued since May of 2023.

CBS News on Sept. 24 reported a newly confirmed case of an elementary student in Minneapolis, bringing the number of confirmed cases in the Twin Cities to over 50.

So far in 2024, there have been 262 reported cases of measles, according to the CDC.

In 2024, cases were reported in Arizona, California, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York City, New York State, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, Wisconsin and West Virginia.

From Jan. 1, 2020, to March 28, 2024, the CDC was notified of 338 confirmed measles cases. None of them resulted in death.

The Maine CDC on April 14 issued a health advisory regarding an “increase in global and domestic measles cases and outbreaks.” The advisory said that Maine has not seen any measles cases since 2019 and made no mention of the May 2023 case it initially reported.

Health risks from measles vaccine outweigh getting the disease

Although media reports sometimes blame the unvaccinated for recent outbreaks, Dr. Liz Mumper, a pediatrician, told The Defender in an earlier interview it doesn’t make sense to assume the unvaccinated are to blame.

She said cyclical outbreaks still occur even in populations with nearly 100% vaccination, such as college students.

The overwhelming majority of the approximately 130,000 measles deaths annually occur in countries in the global south that have weak health infrastructures, according to the World Health Organization. Those deaths, along with measles hospitalizations in the global north, are associated with vitamin A deficiency.

“Measles can be deadly if a child does not have access to safe water and medical care,” Mumper said. “In developed countries, fatalities from measles are very rare.”

Effective treatments include vitamin A in high doses and attention to hydration status, Mumper said.

Other pediatricians who spoke with The Defender said it’s likely better for a U.S. child to get a measles infection than to receive an MMR vaccine.

Dr. Michelle Perro, a pediatrician, said the idea of vaccinating children to protect them from getting measles isn’t completely without merit. “It is worth noting that training the immune system to recognize deleterious foreign pathogens has had public health success.”

However, the risks associated with the MMR vaccine — since it’s nearly impossible to get a single measles vaccine — outweigh getting measles “due to the rise in neurocognitive and other health challenges directly caused by the MMR vaccine” which contains toxic adjuvants, she said.

Dr. Paul Thomas, a retired pediatrician and author of “Vax Facts: What to Consider Before Vaccinating at All Ages & All Stages of Life,” agreed. He said the MMR vaccine is associated with many serious side effects including seizures, encephalopathy, death and autism.

Perro said children’s health took a big hit when Big Pharma and the American Medical Association over 100 years ago forced the public to transition from a natural health platform that included the use of health-promoting diets, herbal medicine and homeopathics to a drug-based system.

Measles can be challenging for children, Perro said, particularly when it’s accompanied by high fevers, diarrhea, uncomfortable rashes and potential negative sequelae such as pneumonia.

Parents must relearn how to manage common viral illnesses, she said. “Be clear, it is much easier to manage a febrile illness in a child than a chronic disease like autism or autoimmunity.”

The Defender reached out to the CDC for comment but did not receive a response by the deadline.

I’m 70 years old. We all had the measles as kids. I don’t remember anyone dying.

Whenever I hear that phrase, "an abundance of caution," I think I am dealing with criminals and liars.